Surrounded by the great swell of the world’s largest ocean, Rangiroa atoll’s coral reef shelters an immense lagoon. A veritable inland sea of gentle waters, the promise of a wanderlust.

Text: Erwann Lefilleul

Photos: Bertrand Duquenne

A sea of oil under an uncompromising sun. Apart from heavy intertropical cumulus clouds following each other in the distance, nothing on the horizon, not a land mass, not a sail. Our Dream Rangiroa catamaran may be in the middle of the Pacific, but there’s not a single long swell on its two hulls. It’s like cruising on a lake.

We’re sailing in an oversized haven. 43 miles long, 17 miles wide, a 79-square-kilometer inland sea that could accommodate the entire island of Tahiti, Rangiroa has become the second-largest lagoon on the planet after Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands.

We’re equally at ease surveying this vast, peaceful expanse, as we have an ultra-comfortable Lagoon 62, usually run as a cabin charter. Bertrand, our faithful travel companion, and I are lucky enough to share the boat with a lovely group of enthusiasts, all of whom love “their” Polynesia.

And as far as the eye can see, the liquid element

The name Tuamotu, and Rangiroa in particular, may ring in the ears of a good number of yachtsmen from all over the world, as well as divers for the famous Tiputa drop-off, but we’re alone on the water. We did catch sight of a handful of sailboats at anchor when we set sail, but since then, we’ve been sailing on a sea out of time, out of its oceanic geography.

When the windows of the domestic airline’s plane appear over the first outlines of the atoll, the mind is struck by this combination of totally opposite notions: immensity and exiguity, strength and fragility. A meagre, featureless strip of dry land scrolls its drifting piece of humanity. Here is the reign of the liquid element. It’s impossible to see the entire lagoon from a bird’s eye view, despite its altitude, or to distinguish between ocean and inland waters without the foamy hint of the offshore swell impaling itself on the protective coral. To measure Rangiroa’s marine influence, it’s not the circumference of its coral ring – 200 kilometers! – but on its width – just 300 modest meters. Despite the 240 known motus, almost the entire three-mile length of the Paumotu atoll is concentrated on just two neighboring motus at the level of the only two navigable passes, forming a tightly-knit offshore microcosm.

Moana, our local skipper, is a prime example of this. Taciturn at first glance, he displays a reserve typical of these islanders at the end of the world, accustomed to self-sufficiency and resourcefulness. A man of the sea in his guts, he has been criss-crossing this great land of freedom since his early childhood. Initially the skipper of day-trip cruisers, for the past four years he has been the official skipper of the imposing Dream Rangiroa. Heading south-west for his first 22-mile crossing, our skipper rarely takes his eyes off the road, scanning the surface carefully for shades of blue. Even if navigation in the lagoon is technically uncomplicated, the random presence of numerous uncharted shoals of the coral potato type means we have to keep a careful watch. The sea is generally very practicable, with moderate north-easterly to south-easterly trade winds all year round, although there is a short chop. On the other hand, when the Mara’amu wakes up, that south-easterly gale accompanied by heavy rain, the water to run is such that it’s not uncommon to have to contend with waves over a meter high. Above all, the trade winds have an impact on the comfort, and sometimes even the safety, of all the anchorages in the western part of the atoll, which are inevitably exposed. For example, it’s rare to be able to spend the night just off Rangiroa’s most famous piece of paradise, the Blue Lagoon, whose silhouette, all coconut palms, soon materializes in the distance in front of our bows.

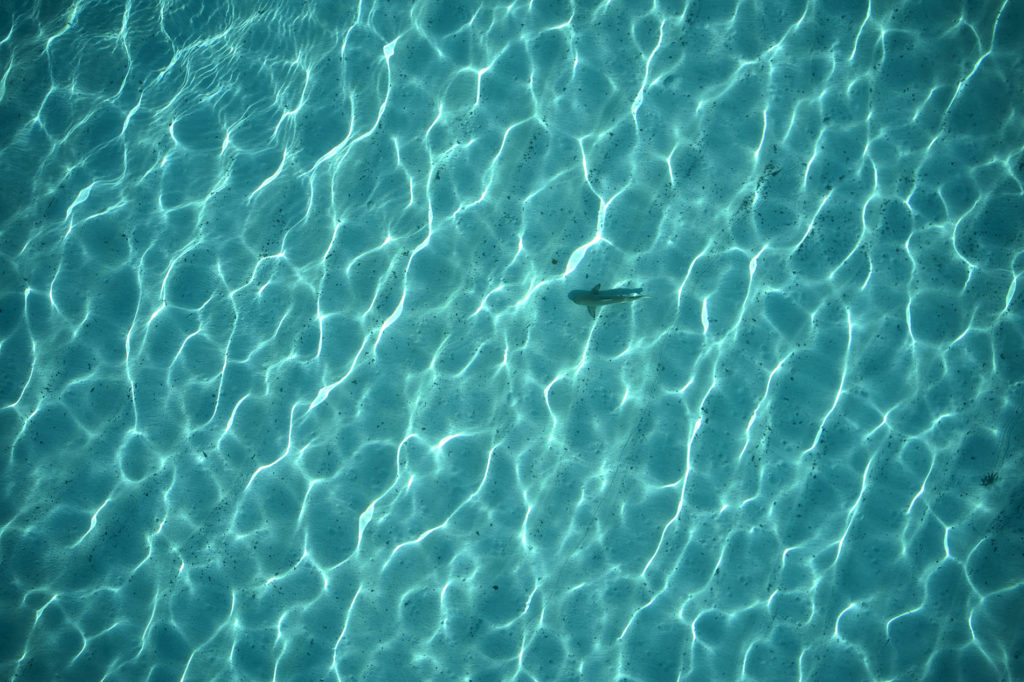

“Sorry, that’s Rangi!”

Surrounded by motus linked by large beaches of dazzling fine sand, an inland lagoon with a multitude of marine colors rivalling in pep, electric, aquamarine, turquoise, azure… In the depths of the Blue Lagoon, amidst nurseries of frantically fearful sharks, the only possible navigation is by paddle or kayak. The shoreline is ideal for leisurely strolls, leading the more adventurous to isolated islets colonized by vindictive colonies of terns and boobies. A short distance away, a carpet of massive coral reefs takes our breath away, before respectable blacktips, simply curious, begin a fascinating encircling circle. Back from our robinsonnades, our delighted faces elicit a disarmingly laconic return from Moana: “Sorry, that’s Rangi!” he says coolly, before quickly breaking into a big laugh, pleased with his effect. The sailor reveals himself, mischievous, deadpan, the mutual acclimatization seems to be taking place.

Simply beautiful, uncluttered and isolated, scorching in the sun, the Blue Lagoon naturally attracts excursion boats and their loads of tourists. One of the motus, equipped with carbets, tables and barbecues, is the epicenter. This is where the flow of visitors is concentrated, and where manta rays, sharks and schools of fish meet, the highlight of a show ensured by generous baiting. Although the noticeable absence of Éole – a rarity that should extend to our entire cruise – deprived us of the opportunity to feel the power of the big sixty-two-footer, the calm did offer us the luxury of keeping our position for the night. By mid-afternoon, as the speedboats dashed north towards the hotels and guesthouses, we found ourselves delightfully alone. A sky of fiery reds punctuates this fertile day theatrically. An inky-black night plunges us without much transition into a motionless darkness barely pierced by the fleeting calls of furtive birds. No strident sounds, no earthy smells. Imbued with this great calm, come the rich hours of dinner, the lightness of the moment, the sharing of memories. The testimonies and experiences of all our companions are so many treasures to be gathered.